“Ninety feet between home plate and first base may be the closest man has ever come to perfection.”

-Red Smith

I’ve always associated with interesting people. One would think, if I do so often enough, some of the interesting is bound to rub off on me, but alas, it is not to be. The party ends, the lights go out, and I go home the same boring sonofabitch I’ve always been.

One of the interesting people I know is a friend I first made in elementary school, Heath Banks. Heath is an umpire. He has called high school games beyond count, worked college games, and an occasional one in Triple A. A year ago he even worked a game in St. Louis’ Busch Stadium.

Once he tried to make it to the big leagues. If you are going to do it, you need to do it by the time you are 25. Heath made his run at the age of 24.

He breezed through the first cuts and earned considerable distinction in the process. He drug that distinction behind him going into the final round. Now he would be calling big league spring training games, and his performance had earned him not a only place in the main park for his first game, but also behind home plate. “On the stick” as they say.

Heath was nervous beyond all get out, but he was also anxious to get the game started and for the butterflies to disappear. Taking his position behind home, he squatted down in his stance and felt a long rip followed by a breeze blowing up his backside. There, on the biggest stage of his career, before the first pitch had ever crossed the plate, in what he had hoped to be his finest hour, Heath had ripped the seat right out of his pants. The distinction behind him would do little to hide it.

“It was horrible. All I could think about was that everyone in the stands could see my whitey tighties. I wanted to crawl in a hole and die. There was nothing I could do. I couldn’t stop the game. I had to get on with it.

When the pitches started coming in, I could hardly see straight. I had no idea where they were. My strike zone was all over the place. Around the third inning an instructor came down and asked, ‘What the fuck are you doing out there, Banks? You look like a god damn clown.’

After that I kind of knew it was over. I got sent down to the bottom of the deck at some little, out of the way field. After a game or two I realized no one was coming by to see how we were doing, and they were never going to come. I spent the rest of my time drinking beer with the guys.”

Fifteen years after his tryout, I got a call from Heath mid-October. “Got a few World Series tickets to game 6 in Kansas City. Any interest?”

“Hell yes.”

It would be a stretch to call me a fan of baseball. It’s not because I don’t enjoy it. I enjoy it above all other games. It would be a stretch to call me a fan because I know so little about it, especially when it comes to one of the things which separates it from all other games: its grand mountain of statistics.

Yet here I was, three or four rows up from the outfield and forty feet from the foul pole. Looking up at it, it appeared as though it was a hundred feet high. I thought of how a ball might be hit down that line and over the wall. Half the country would hang in suspense on whether it was fair or foul. Perhaps it would be part of a moment that would live forever in baseball lore. I would be among the first handful to know, a few seconds ahead of those watching at home, a few milliseconds before it would be added to the mountain of statistics already mentioned.

Pleasure doesn’t lie in keeping a secret. It is found in knowing first what everyone else will come to know later.

All told, three of us had went down to see Heath, who was seeing all the home games that series. We spent the day in good company, eating the best food and having the occasional beer. I suppose it was the latter that had left me thinking I should share my observations on the sport I know so little about with the guy who actually gets paid to observe it. He didn’t seem to mind.

“Heath, I think the thing about baseball is the pauses. No other sport has them like baseball, and that’s too bad. During those pauses baseball places on you the full weight of the moment to come. The deep breath the pitcher takes just before delivery, the flight of the ball to home, all leave you waiting anxiously on the swing of the bat.”

Yes, I thought, whoever invented baseball knew a thing or two about anxiety and had simply built a game around it.

For Royals fans during that game, the potential of the second inning was realized beyond their wildest expectations. They would score 7 runs during it, and we whooped and hollered and drank more beer during the forty five minutes it lasted. Any anxiety drizzled out with the Giants hopes, and for the rest of the game the joy continued unabated.

“So I was offered some tickets to the VIP party afterwards. What do you all think?” asked Heath.

We were speechless.

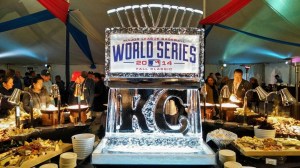

Beyond the outfield wall, in the white tents pitched inside a wrought iron fence, everything was complimentary. We judiciously used the free food and beer to bring our dollar cost average down for the food and beer we purchased during the game. When the dust had settled, we had ate and drank cheaper than any happy hour special Des Moines could boast of, and we had done so with the rich and famous, or at least their second cousins.

We headed back to the hotel, where we happened onto one of KC’s brightest stars, Mike Moustakas. The evening had been full of so many “I can’t believe that just happened moments,” I didn’t doubt that had happened at all. We recharged, and headed for a bar just down the street from where we were staying, called ‘The Quaff.’

“The Quaff is an ‘umpire friendly’ bar. All the towns have them. It’s a place the umps can go after a game where the owners ensure they can enjoy a little peace and quiet,” Heath told us.

As we walked in the door, the bar was a series of three, long, narrow corridors. We were in the first one. Along one wall stretched the bar, down the center was a narrow aisle, and stretching along the backside was a series of booths that would hold two a piece comfortably and four if it had to. We took a booth.

Occupying the rest of them and lining the bar were Royals fans. Light blue hats and light blue jerseys were all oriented to the old, grimy, color televisions, which had probably also broadcast the last World Series the Royals were in. They were still showing post game coverage on the MLB Network. These fans had watched the entire game from these seats, and we looked at each other, quietly sharing the secret that we had enjoyed the game from better ones.

We all had a dab of light blue ourselves. Most of ours had been purchased only a few hours prior.

Quietly we began to talk the way people always talk after the unbelievable happens. At least three of us, giddy as schoolgirls, did. Heath was already on his third game of the series, and by now was old hat at it. He just sat and smiled the way people always smile when they give the gift that lights up the face of someone else.

All of the sudden he looked up and said, “They’re here.”

Coming through the door into the sea of blue was the World Series umpire crew. There was Des Moines native Eric Cooper, his wife Tara, and their son. Cooper’s shaved head was in a Notre Dame hoodie, and behind it was the flat top of Jeff Nelson. Behind all of them was Ted Barrett, the only major league umpire to have been behind the plate for two perfect games. The Coopers should have been pretty familiar with Barrett. They not only umpire together, but Barrett, an ordained minister, had married them. Jim Reynolds, also umpiring the 2014 World Series, was married by Barrett as well.

As they walked around the sea of blue before them, not a single hat turned, and not a single “Hey, aren’t you….” was heard. Everyone remained oriented to the old color TVs, while we got up to join them and make our way to the back of the bar. We passed through the second corridor, housing pool tables, a dart board, and a jukebox full of Tom Petty albums, and landed, safe at third, in the back one housing the kitchen, the restrooms, and a couple of dim lit lights.

There in seclusion, we spent an hour or two, putting a cap on a hell of a good night. Just before we left, I realized I was all wrong about baseball. It had nothing to do with finding anxiety in its pauses and its base paths. We find that daily in our own lives. Instead it has everything to do with finding peace, even if it had left your ass hanging out in the breeze one day.