The morning after found us in the Art Institute of Chicago. Towards the end of our time, I caught the woman who had brought me standing before a portrait. It was a portrait everyone looked at, and I was trying to find some hidden gem, among works that were all gems who had mostly lost part of their luster and most of the appreciation of their rarity since they were all gathered here under one place.

“I suppose you’ve seen this one too.”

“No, I haven’t.”

“You’re kidding me? American Gothic, Nighthawks, the picture on the shore with the little girl that stares at you, and you never taken the time to look at this? This one is amazing.”

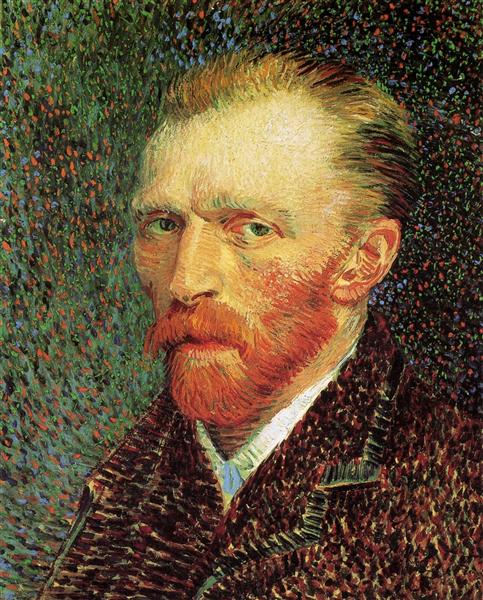

It was amazing. The paint was layered so thick it hung like flesh on the bone. There was a texture, a human texture to it, and it stood out from the stair-stepped frame that had brought you down to its surface. His cheek alone looked to rise half an inch from the canvass.

“I’m not even sure how long I’ve been looking at it. It’s got this background of colors that contradict one another, but somehow his image ties them all together. You can pick a hue from the background and look at him and find it every time. I can’t decide what it means.”

“What do you think it means?”

“I thought it meant we are all made up of all kinds of contradictions, but I wonder if he wasn’t trying to say that in our bringing them together we make some sort of sense of them.

Standing here, it’s like he’s going to come out of that wall or something. I think that’s the quality I most admire. I like the ones that make you forget it’s a painting.”

The past is present. People say you should “move on” or “let the past be the past,” but the past is present. Maybe all “moving on” is, is getting to a place where you can look at ourselves with nothing more than curiosity with which we look at them, divorced from all the intensity that was then.

We think forever is a series of nows without end; the present followed by an endless supply of the present. It’s so linear. What if forever is simply viewing past, present, and future, all at once?

Vincent van Gogh painted over 30 self-portraits. The Art Institute of Chicago lays claim to a self-portrait he did in the spring of 1887. Penniless, he could not afford to hire anyone to pose. Struggling, there was no one who would pay him to paint their own. To perfect his technique he scraped up enough to buy a mirror and use himself as a model.

He painted the image as he saw it, his right is actually his left. Surely he knew what he was looking at, but he did not seem to correct for it. Most of us stumble out of the shower, face the mirror, and never even consider that the right of our reflection is our left. Even in that most perfect reflection, we are not who we seem, and those around us stake a claim to seeing us better than we can see ourselves.

In his self-portraits, we see the artist as the artist sees himself and as he sees us.

“I strongly urge you to study portrait painting, do as many portraits as you can… We must win the public over later on by means of the portrait; in my opinion it is the thing of the future.”

-Vincent van Gogh to Emile Bernard